Equality through Religion in Transatlantic Slavery Art

savannah240

2144

Equality through Religion in Transatlantic Slavery Art

by Savannah Teekel and Daniel Joiner

by Savannah Teekel and Daniel Joiner

Past documents and images may not have survived the many years of slavery, war, and natural disasters quite like the Bible. However, the era encompassing the transatlantic slave trade left a trail of images, poetry and political propaganda in the wake of its mass transportation of humans as goods. Englishman William Blake’s “Little Black Boy,” composed in 1788 and published as one of the Songs of Innocence, and American Abel C. Thomas’s The Gospel of Slavery: A Primer of Freedom, published in 1864 under the pseudonym of Iron Gray, show us how poets on both sides of the Atlantic used similar methods to critique the use of religion to justify slavery. The people of America and Europe both utilized a misinterpretation of the Bible to condone slavery, and perpetuate it around the “New World.” Some honest people of Britain and the Americas knew that religion fueled the wealthy trade leader’s plan for building a new profitable settlement, advancing colonial imperialism, and maintaining power structures. Blake and Thomas tell us that through faith men can see each other as equals; their emotional poems and images expose the flaw in religiously backed slavery. Although they lived on separate sides of the Atlantic and in different time periods, they still felt compelled to discuss and dismantle the ideologies surrounding slavery. African-Americans were forced into a false Christianity, which proved to support the slavery status quo. It called for the slaves to be happy with their status as slaves, and also recommended complacency and a lack of questions. All of these reasons were prevalent in both England and America as arguments for the continuing of slavery. Since the beginning of Christianity, social groups have interpreted the word of the Lord in their own ways. However, from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, there were not many people, much less slaves, capable of challenging those interpretations.

|

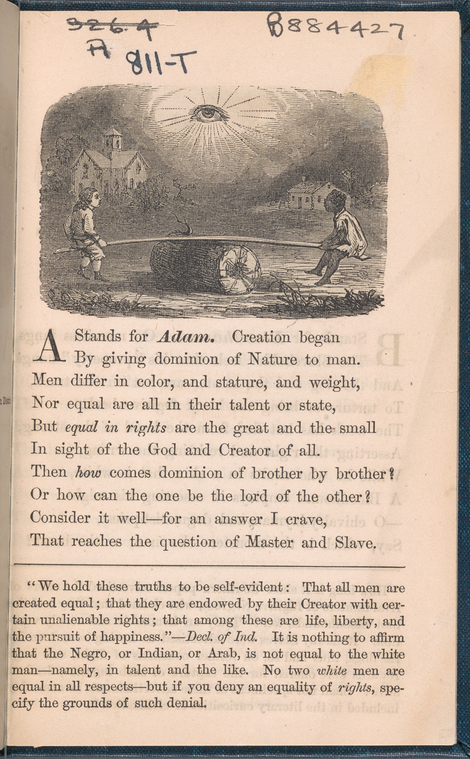

Once enlightened individuals started pointing out these cruel interpretations to the masses a new idea was born and became popular not only to slaves, but to the moral citizens in society. The Bible’s references to how man should live and what virtues he should seek, allowed for Europeans and new settlers of America to condone and promote the use of brutality to convert and enslave in the name of the Lord. The influence religion had on enslaving and converting people, whom they assumed to have an insignificant and pagan religion, was typically powered by wealthy Europeans and government officials. Yet authors, ministers and abolitionists took action proclaiming their opposition of the hierarchy for the world to read. In an image (Figure 1) from Thomas’s book The Gospel of Slavery: A Primer of Freedom, we see a representation of equality through the children’s differences. There is an all seeing eye of the Lord watching over them, or it may represent a symbol of knowledge which destroys the ignorance that enforces the evil of slavery. This eye is looking over two boys on a seesaw who are seemingly equal individuals in this picture. The noticeable differences in the images are in the boys’ skin colors and the buildings behind them, which may represent their class levels. The balanced position of the seesaw and the centered eye located vertically above the fulcrum of the toy portray equality of the boys with no regard to race or social class. In fact, because the all seeing eye is the all seeing eye of the Lord, and the illustration does not appear to acknowledge race and class, the reader is led to infer that the Lord doesn’t see race and class as important. In Thomas’s poem “A Stands for Adam” he alludes to the Declaration of Independence when he says, “But equal in rights are the great and the small/ In sight of the God and Creator of all” (3). While the boys appear to be equal in size, height, age and all other physical qualities there is a strict sense of inequality knowing that one will become the other’s master and one is born into slavery. The idea that since the creation of humankind one individual was greater than the other is hard to grasp in a society of logical people who are taught faith. It is even harder to grasp in a society where almost every individual subscribed to a belief system that revolved around love, compassion, and sacrifice for your fellow humans regardless of nationality. This is where we see that misguided individuals gained power through enforcing immoral codes. Christianity’s Golden Rule is “do unto others, as you would like done unto you,” and it is senseless that the abominable institution of slavery was not only condoned but perpetuated in society with that type of golden rule.

|

|

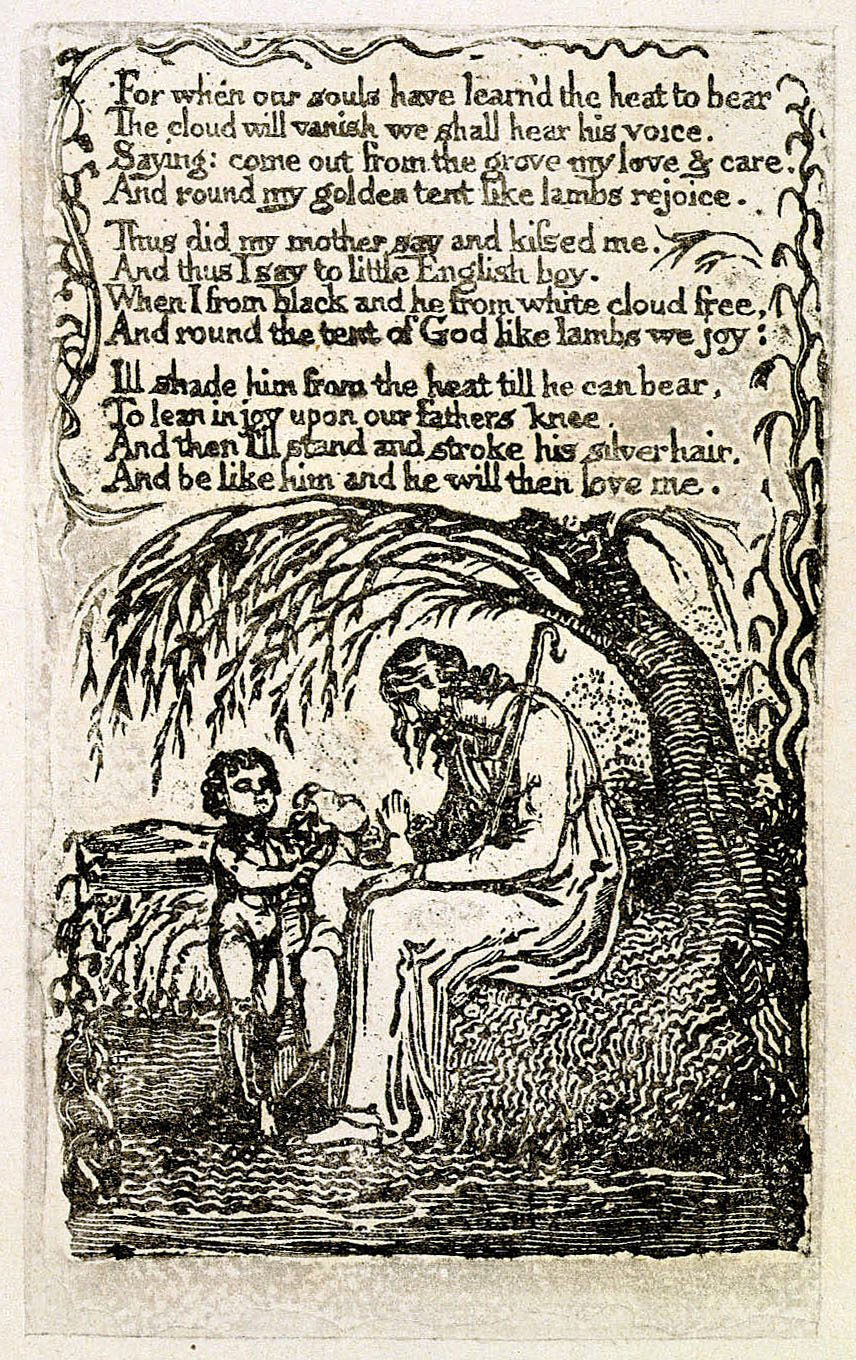

The engraving that accompanies one of William Blake’s copies of “Little Black Boy” (Figure 2) illustrates his attitude toward slavery and influence on transatlantic slavery. The picture of a young boy and his mother talking under a tree in the setting sun opens the poem with a peaceful scene, a seemingly virtuous image. The mother and son are shown to have a loving and stable relationship, which was something that usually was not afforded to the two as slaves. This relationship makes them more relatable to the reader. The last stanza in “Little Black Boy” further exemplifies Blake’s idea of racial equality. The speaker says, “I'll shade him from the heat till he can bear, / To lean in joy upon our fathers knee. / And then I'll stand and stroke his silver hair / And be like him, and he will then love me” (29-32). The first thing the black child will do is protect the white boy; however, this is not to be confused with forced servitude. Because they are equal, it is the black boy’s choice. Blake shows the black boy is capable of helping the white boy out of his own volition without having to be forced to do so. That is a very Christian like quality that one would not expect from someone who was not equally spiritual in the eyes of God.

|

They both sit at Jesus’s side as equals. Their closeness and intimacy in the poem is like two brothers seeking their father’s comfort. Blake shows the black boy and white boy on equal footing spiritually and physically, suggesting that the perceived inferiority of the slave is nonexistent. In God’s eyes, they’re equal, and perhaps in humanity’s eyes they should be as well. It’s peculiar that the religious freedom many Europeans sought to have in the New World would come from the oppression of other people. The Christians of Europe felt empowered by their understanding of the Bible and took what they could to build an empire stretching from Europe to America. The audience for these harsh poems and pictures was the English and Americans who allowed such cruel mistreatment of humans for so many centuries.

|

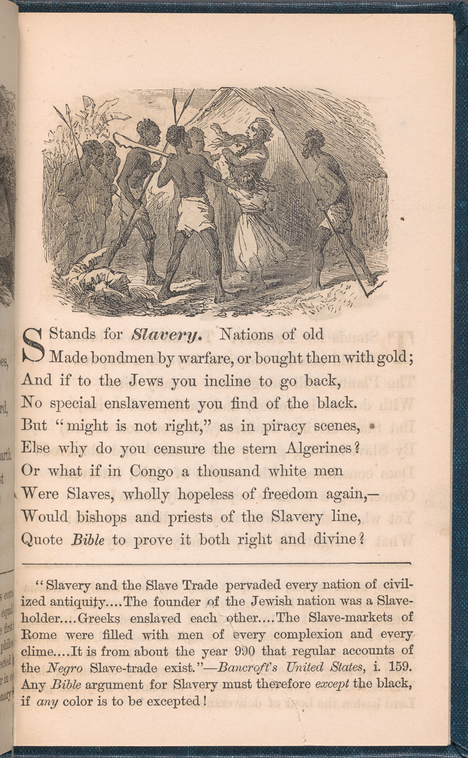

The influence of European and American Christians on African peoples shows that through their self-serving interpretation of the Bible they justified their horrid involvement in the enslavement of millions of people over many centuries. “S Stands for Slavery” in Thomas’s book (Figure 3), with the scene of white slaves in the Congo surrounded by black slave owners and scared for their lives, reverses the roles of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. The lines, “Or what if in Congo a thousand white men / Were Slaves, wholly hopeless of freedom again,” question if one would use the Bible to justify enslaving of these people (21. 7-8). He wonders if white men were subjected to the same treatment as blacks would religious people still use the Bible as a divine justification of slavery.

|

Thomas admonishes those who rely on the Old Testament to justify slavery by saying, “And if to the Jews you incline to go back, No special enslavement you find of the black” (21. 3-4). He argues that even in the Old Testament slavery wasn’t reserved for only blacks like it is in his society.

Works Cited

Blake, William. “Little Black Boy”. The Oxford English Book of Verse. Ed. A. T. Quiller-Couch. Clarendon: Oxford, 1919. Jan. 1999. Bartleby.com. Web. 28 Oct. 2014.

Fig. 2. Blake, William. The Little Black Boy. 1789. Yale Center for British Art. New Haven, CT. The William Blake Archive. Web. 20 Nov. 2014.

[Thomas, Abel C.] The Gospel of Slavery: A Primer of Freedom. New York, 1864. Anti-Slavery Literature. Web. 25 Nov. 2014.

Fig. 2. Blake, William. The Little Black Boy. 1789. Yale Center for British Art. New Haven, CT. The William Blake Archive. Web. 20 Nov. 2014.

[Thomas, Abel C.] The Gospel of Slavery: A Primer of Freedom. New York, 1864. Anti-Slavery Literature. Web. 25 Nov. 2014.

Fig. 1. [Thomas, Abel C.] A Stands for Adam. 1864. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Fig. 3. [Thomas, Abel C.] S Stands for Slavery. 1864. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.