LeBourgeois sp2010

leeyesa

550

Transcendentalism, at first thought, typically brings to mind a couple of different things. The first of these things is usually the name Emerson followed by Thoreau, and the vague feeling that those two names were important regarding nature or politics and wasn't Walden Pond involved somewhere? In reality, the term "transcendentalism" covers ideas ranging from anarchy to passive resistance to thoughts on religion to the abolitionist movement. Transcendentalism is in essence based off overcoming the physicality of life and instead focusing on the intuition; it rejects government and religion, though it does not proclaim that God does not exist (exactly the opposite) or that it is realistic to believe anarchy is achievable, at least at the time being.

For a group almost entirely run by theories, the transcendentalists were particularly effective at expressing and organizing opposition to slavery. Slavery, ownership of one human by another, particularly rubbed them the wrong way: it goes against almost everything transcendentalism supports and believes. Destroying both the spiritual and emotional capacities of people, slavery was the ultimate foe.

For a group almost entirely run by theories, the transcendentalists were particularly effective at expressing and organizing opposition to slavery. Slavery, ownership of one human by another, particularly rubbed them the wrong way: it goes against almost everything transcendentalism supports and believes. Destroying both the spiritual and emotional capacities of people, slavery was the ultimate foe.

|

It is interesting to discover that Emerson was in fact a reluctant supporter of abolition. A discussed in the article, Emerson was basically drug by his heels into the issue, resisting the entire time. Originally Emerson's goal was to stay out of the slavery issue altogether, but with a little help from his friends, (Channing, Garrison, Mott) Emerson eventually landed in the middle of the situation. His belief that reform stems from the individual not society has much to do with his initial refusal. Why should he delve into abolition when clearly the slaves were inferior? Their freedom lay with them and their slave-holders, not with society, and if they wanted to be free they had to begin the process. However Emerson's Divinity speech thrust him centrally into controversy and the more open minded and outspoken he became. Emerson inevitably reversed his thoughts on abolition and became "an avowed abolitionist." His reluctance is interesting because of what it symbolizes: that transcendentalists weren't opposed to change. In fact, their openness to change was key to their involvement in the freeing of the slaves.

|

|

This article, written by Robert C. Albrecht, discusses how important Thoreau's speech regarding John Brown was to him. Painstakingly altering his Journal to fit the needs of his audience, adding wit, toning down language, and adding the sense of genuinely knowing Brown (despite only having met Brown once or twice,) Thoreau's intensity is still obvious. Bordering on obsessive, Thoreau's dedication to sharing Brown's abolition message is truly impressive. Looking back at Thoreau's Journal, Albrecht shows how almost sporadic Thoreau's thought process for the speech was. His notes are scrambled, and almost up until the day of the speech there is hesitation in Thoreau's words--but he spoke regardless, with passion and fervor.

|

|

This article quite simply demonstrates how Thoreau, Garrison and Dymond argued and collaborated with each other. All three are proven intellectuals and this proof is important--it gives authenticity to their words and ideas; these men are educated, therefore their writings are thought-out and well presented. More Christian than Thoreau, Garrison and Dymond's works speak volumes about morality, slavery and the importance of non-violence. Though Thoreau's backing of John Brown caused opposition from Garrison and Dymond, they continued to collaborate. The importance of these associations cannot be undermined, without their constant questioning of each other the transcendentalist's influence would have been greatly reduced.

|

|

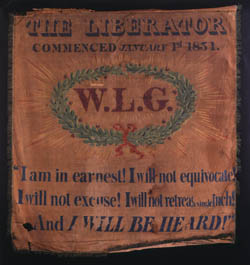

This the the most illuminating piece. The letters between Garrison and Vashon give an inside view at what the men truly believed. Much less pretentious than a speech per say, rawness and emotion for what is really the first time are exposed. It is in these letters that the realization of how close to the heart abolition was to the transcendentalists becomes apparent, how necessary the freeing of the slaves was not only for the slaves themselves but also for the transcendentalists and abolitionists. The sense that Garrison would literally rip his heart out for Vashon is overwhelming, and the respect the two men have for another is equally impressive. Garrison's personal letters to a freed slave are proof that the abolitionist cause was not merely a fad sweeping the nation, but an intense battle between wrong and right.

|

|

Thoreau was an avid supporter of John Brown even through Brown's controversies. Brown, a rather extreme abolitionist at times, excited Thoreau to a degree that Thoreau left his "seclusion" to speak on Brown's behalf. It is rare that Thoreau became so passionate about another person, and this within itself says much about Thoreau's dedication to the ending of slavery.

|

|

Margaret Fuller was an extremely unique woman for the 19th century. A champion of women's rights, she strayed from the typical path of other women during the time and chose not to participate in the abolitionist cause. There is a line between abolition and anti-slavery, and Fuller had identified it and chosen her side. Once deeming abolitionists "madmen," her time in Italy showed a new perspective, one where she sympathized with the abolitionists and wished God upon them. But she was still indifferent, and throughout here life this sentiment would not change. Despite her close friendships with Emerson, the Alcotts, and Theodore Parker, she steadfastly disliked the excess of abolition, distrusted political parties, never once straying from her strong anti-slavery beliefs. Fuller was genuinely ahead of the game; her desire to liberate all--slaves and women--was more radical than the abolitionists'.

|

A compilation of varying sources shows how widespread, varied and genuine the transcendentalists' opposition to slavery truly was. Not a cause with mild support of only Thoreau or Emerson, abolition and the ending of slavery was a main focus and uniter within the transcendentalists. Not afraid of the media nor of their peer's opinions, the transcendentalists followed where their intuition led them--this time down the road of freedom.