The Goddess of Love and Beauty: Dante Rossetti's Venus

Amanda Stancati and Eva Ho

|

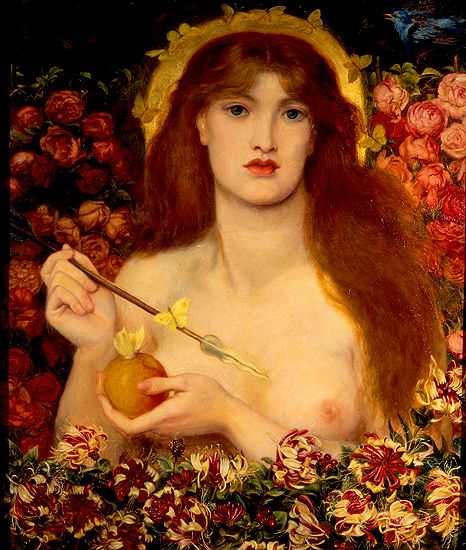

The perception of beauty was quite different in the

nineteenth century. In 1868, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, an English painter and

poet, created Venus Verticordia – a

sonnet with a corresponding painting.@Dante Gabriel Rossetti, "Venus Verticordia" This is an example of one of Rossetti’s

“double works of art”, in which he produces a set of visuals and texts that are

meant to elaborate upon each other. Rossetti was often criticized for his work

because he did not conform to the typical mold, but decided to challenge the

Victorian standards of beauty instead. Venus is universally recognized as the

goddess of love and beauty. However, beauty is subjective and the ideals of

beauty are always changing due to individual tastes. The poem is in the English

sonnet form and written in iambic pentameter. It first appeared in the 1868

edition of Notes on the Royal Academy Exhibition.@Dante Gabriel Rossetti, "Venus Verticordia". The associated portrait is an oil

painting that features model, Alice Wilding.@Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Venus Verticordia. 1864-1868. Russel-Cotes Art Gallery, UK This exhibit will

question and explore how Rossetti constructs his Venus through the text and

visuals. By analyzing how mythical and biblical influences reflect

Pre-Raphaelite artwork, this exhibit will examine how Venus

Verticordia reflects Rossetti’s ideal Venus

and the representation of the Victorian woman. |

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

During the nineteenth century, British theorist, Mary Anne Schimmelpennick, developed an aesthetics concept. The basis of this concept led to an influx of quasi-scientific classification systems that claim to have the ability to decode an individual’s psychological state based on their physical features@"Pre-Raphaelite Challenges to Victorian Canons of Beauty". pp.16. These ideas were very popular at the time and the physical prejudice strengthened the segregation of social classes in England. There was an increasing fear of the emerging middle-class during the nineteenth century, so as a result, most people would blindly followed these systems. The PRB greatly opposed this concept because it goes against the law of nature.

1860s: Shift in Artistic Direction

|

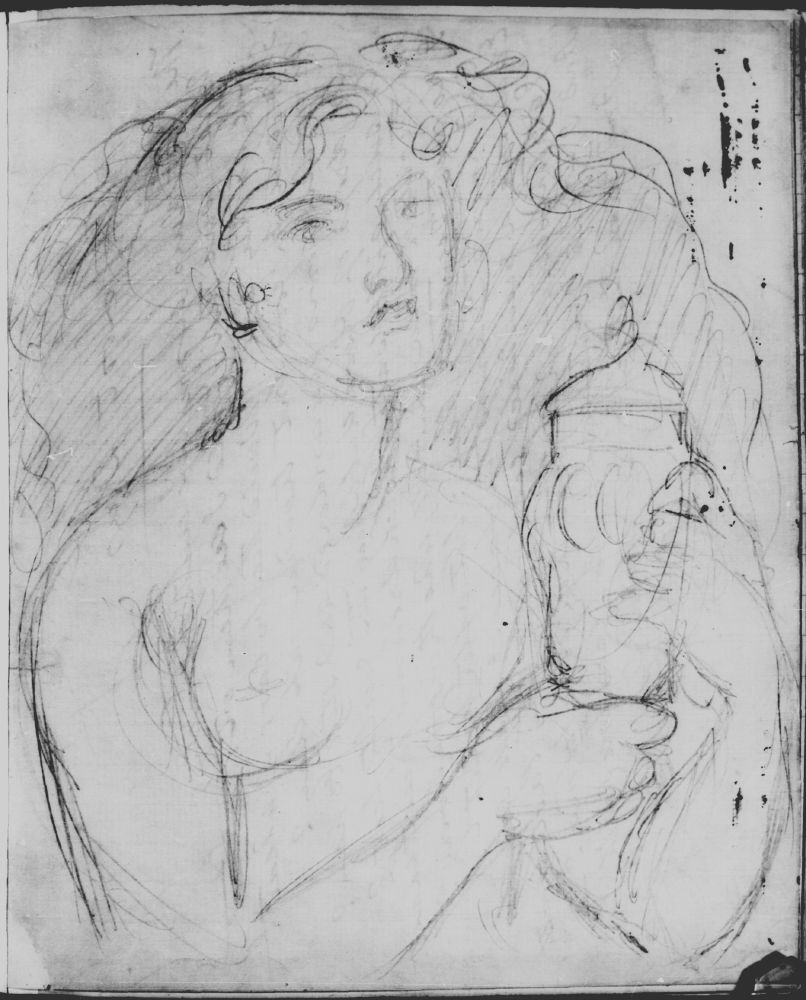

Many critics believed that Rossetti produced his best work around the 1860 period. The linear clarity and vibrant colours were some of the techniques from Italian primitive art that he would try to emulate. Upon the encouragement of his artist friends, Rossetti was able to develop his signature style with watercolors throughout the next few years.@Jerome McGann. Dante Gabriel Rossetti: and The Game That Must Not Be Lost. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000) Eventually, his artistic vision changed in the way ideas were portrayed on canvas. In Rossetti’s earliest paintings, such as The Girlhood of Mary Virgin@Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Girlhood of Mary Virgin. 1849. Tate Gallery, London., the models were composed in a very simple manner – full-length figures placed in linear form. This was very different from his portraits post-1860 where the center of attention would concentrate on the upper part of the body, creating a tighter focus on the subject.@Dante Gabriel Rossetti: and The Game That Must Not Be Lost. pp. 118 When Rossetti produced Venus Verticordia in 1868, many art enthusiasts criticized it heavily. The painting, which features a woman with an exposed chest, was said to be coarse and tasteless. However, what the public perceived as vulgarity was actually interpreted by Rossetti as an ideal of how the embodied body of the soul should function. This concept had been on his mind for a long time, but it was not until the 1860s that he took the initiative to explore the idea through his paintings. Art critics did not welcome Rossetti’s new approach and interpreted them as technical flaws. His brother, William Michael Rossetti, wrote that Rossetti was fully aware of the Victorian aesthetic principles, but he purposely went against the norm to develop himself as an artist.@Dante Gabriel Rossetti: and The Game That Must Not Be Lost. pp. 110 Rossetti’s favorite subject of choice in his paintings and poetry were women. By featuring women in his work, he was able to explore the different facets of beauty and feminism.@Johnson, Wendell Stacy."D.G. Rossetti as Painter and Poet".Victorian Poetry.Vol. 3, No. 1 (Winter, 1965), pp. 9-18. West Virginia University Press. Venus Verticordia defines the shift in artistic direction that Rossetti went through during the 1860s. In order to create a sensuous and erotic tone, he would focus on close-ups of the models to express female sexuality. This artistic approach was common in Rossetti's later works and it led to a series of paintings that are critical in the complex study of Rossetti’s ideal Venus. |

The Goddess of Love and Beauty: Dante Rossetti's Venus

Amanda Stancati and Eva Ho

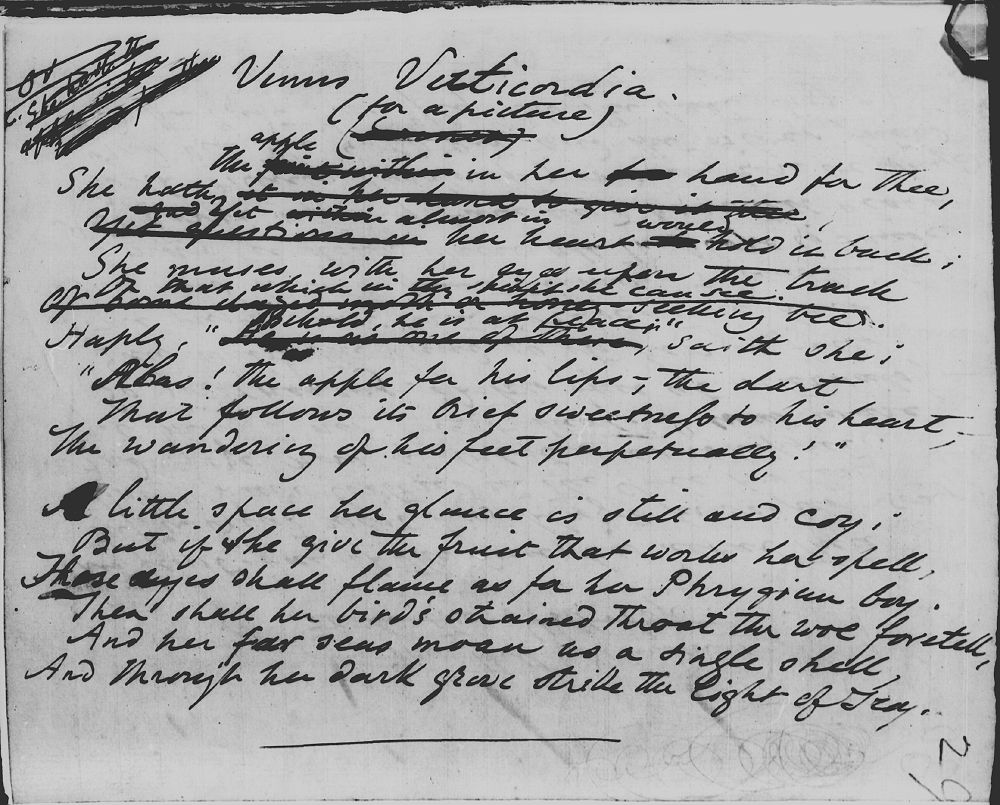

Analyzing the text of "Venus Verticordia"

Yet almost in her heart would hold it back;

She muses, with her eyes upon the track

Of that which in thy spirit they can see.

Haply, ‘Behold, he is at peace,’ saith she;

‘Alas! the apple for his lips,—the dart

That follows its brief sweetness to his heart,—

The wandering of his feet perpetually!’

A little space her glance is still and coy;

But if she give the fruit that works her spell,

Those eyes shall flame as for her Phrygian boy.

Then shall her bird's strained throat the woe foretell,

And her far seas moan as a single shell,

And through her dark grove strike the light of Troy.

|

The painting, Venus Verticordia, elicits biblical and mythological references that can be interpreted in light of the poem by Rossetti. With motifs like the apple, halo, flowers, and arrow, each explicitly representing something more, the relationship between the poem and painting leave room for discussion.The apple is a significant aspect of the painting. It is a reference to the apple from the forbidden tree of knowledge that Eve ate in the Garden of Eden that caused the fall of man and original sin. Additionally, it is a reference to the apple that Paris offered Venus in Greek mythology in appreciation of her exquisite beauty. The first two lines of the poem develop the idea of temptation and can be interpreted in many different ways. Venus possesses the apple, or symbolically, the power to defy God, gain knowledge, exercise her sexuality, and influence Adam, or men in general. But, in the case of Paris and Venus, the apple is used as a sign of beauty. Yet in the poem, Venus is hesitant to give the apple away, demonstrating her ambiguous nature that will later be discussed further. The apple is referred to as a “dart,” having negative connotations, and is meant to be aimed at a target, in which the sweetness is only momentary and then pain prevails. In the second stanza, it is stated that the apple “works [Venus’] spell.” This reference to a ‘dart’ and the concept of a ‘spell’ demonstrates the female power associated with knowledge, beauty, and sexuality, but is always followed by 'woe'. Although Venus is hesitant to give the apple away, she exercises her freedom in doing so, and is triumphant over the man. |

The Goddess of Love and Beauty: Dante Rossetti's Venus

Amanda Stancati and Eva Ho

Vision of Ideal Beauty: The "Rossetti Woman"

While the PRB were scrutinized for using unconventional art techniques, Rossetti was mainly condemned for the sensuous nature of his paintings. This new style came about in 1860s when Rossetti experienced a shift in artistic vision. From exploring new meaning in visuals, Rossetti was able to compose his own sense of ideal female beauty. The women in his paintings did not conform to the mold of the demure and fair Victorian maiden. Instead, he constructs the idea of a “dark Venus” in his paintings with powerful Amazonian structured bodies and bold, direct gazes.@"Pre-Raphaelite Challenges to Victorian Canons of Beauty".pp. 30 There was an erogenous emphasis on areas around the décolletage, mouth and hair. The models were usually loosely dressed and exposed more skin than what was considered appropriate back then. Other typical characteristics that he would accentuate include: full, red, fleshy lips, sleepy eyes, profuse wavy hair and long neck. The general public despised these pieces and identified them as vulgar because it went against conservative Victorian beliefs. Through his paintings, Rossetti argues that women should embrace and not suppress their sexuality because real beauty is confidence.

Much like The PRB's mission statement to include all facets of nature into their art, Rossetti implies that we need to accept our flaws since it is impossible for everyone to assimilate to a certain code of standards. This is demonstrated and critiqued through the execution of Venus Verticordia. Initially, the model for this painting was a cook Rossetti noticed in the streets. However, her face was substituted with Alice Wilding's, a model whom Rossetti often featured in his paintings to idealize sexuality@The Rossetti Archive. Venus Verticordia. (For a Picture.). In later years, he made several reproductions of Venus Verticordia using different models. Similarly to the modern woman, Venus has multiple identities that doubles itself in this "double work of art". Women should be able to express their individualism and embrace difference sides to them. Through Rossetti's eyes, Venus is no longer one-dimensional but transformed into a woman with depth and substance.

The Fallen Woman in "Venus Verticordia"

|

The fallen woman was a common topic in Victorian art and literature,

especially in Pre-Raphaelite painting. It was based on the idea of

promiscuous females, which relates to Venus because of her exposed

breasts, the arrow, and the apple. Female sexuality in Victorian times

was repressed and recognized only in relation to the male.@Need, Lynn. "The Magdalen in Modern Times: The Mythology of the Fallen Woman in the Pre-Raphaelite Painting."Oxford Art Journal.Vol 7 (1984):26-37. Web.

Nead discusses the “feminine ideal” versus the “fallen woman” and she draws the comparison between the Madonna and Mary Magdalene, two biblical figures. This comparison supports the irony of both the apple and halo being present in the painting. Nead says fallen women were threatening because of their public nature, disease, disruption of families and society, and the reflection of low societal morality. However, the prostitute can also be described in terms of her innocence, making her seem tempted and ashamed,@Need, Lynn. "The Magdalen in Modern Times: The Mythology of the Fallen Woman in the Pre-Raphaelite Painting."Oxford Art Journal.Vol 7 (1984):26-37. Web. hence the halo. The fallen woman is sexually deviant and is seen in the outside, immoral world, whereas the feminine ideal remains in the home which is pure.@Need, Lynn. "The Magdalen in Modern Times: The Mythology of the Fallen Woman in the Pre-Raphaelite Painting."Oxford Art Journal.Vol 7 (1984):26-37. Web. Likewise, Venus is placed outside in the wild among the flowers in the painting, and not within the domestic sphere. Venus Verticordia may have also been viewed as a fallen woman during the nineteenth century because of her liberated sexuality as seen through her nudity (in the painting) and her assertion of power (in the poem). |

The Goddess of Love and Beauty: Dante Rossetti's Venus

Amanda Stancati and Eva Ho

Public Reaction: Rossetti vs. Ruskin

|

Venus Verticordia was not one of Rossetti's most significant pieces, but it was particularly infamous for being the cause behind the end of Rosetti and Ruskin's friendship. John Ruskin was an art enthusiast, renowned critic and one of Rossetti's closest friends.@Helen Rossetti Angeli. Dante Gabriel Rossetti His Friends and Enemies. (London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd., 1949) The two have a patron-artist relationship and Ruskin often bought paintings from him. Rossetti agreed that they were both on par in terms of intellect but felt that Ruskin did not have an infallible perspective of art like he did. Already experiencing mixed emotions about Rossetti's new style of artwork, the appearance of Venus Verticordia pushed Ruskin to his limits until he was no longer able to hide his disgust. In a series of letters addressed to Rossetti, Ruskin attacks the way in which he handles the oil paints and how coarse the overall tone is.@William Michael Rossetti. Rossetti Papers, 1862-1870.London: General Books LLC, 2009. While Rossetti's paintings did not resonate with the general masses, there were a few select groups who accepted his mode of aesthetics.@"Pre-Raphaelite Challenges to Victorian Canons of Beauty". pp. 31 It was acknowledged earlier that The PRB had an avant-garde feel to their work because they went against the norm to envision new methods that were ahead of their time. As a result, Rossetti's productions became popular within groups of advanced artists and later set the founding basis of the Modernist art movement.

|

The Goddess of Love and Beauty: Dante Rossetti's Venus

Amanda Stancati and Eva Ho

Endnotes

1 Dante Gabriel Rossetti, "Venus Verticordia"

2 Dante Gabriel Rossetti, "Venus Verticordia".

3 Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Venus Verticordia. 1864-1868. Russel-Cotes Art Gallery, UK

4 Casteras, Susan P."Pre-Raphaelite Challenges to Victorian Canons of Beauty".Huntington Library Quarterly.Vol. 55, No. 1 (Winter, 1992), pp. 13-3. University California Press.

5 "Pre-Raphaelite Challenges to Victorian Canons of Beauty". pp.16

6 Jerome McGann. Dante Gabriel Rossetti: and The Game That Must Not Be Lost. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000)

7 Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Girlhood of Mary Virgin. 1849. Tate Gallery, London.

8 Dante Gabriel Rossetti: and The Game That Must Not Be Lost. pp. 118

9 Dante Gabriel Rossetti: and The Game That Must Not Be Lost. pp. 110

10 Johnson, Wendell Stacy."D.G. Rossetti as Painter and Poet".Victorian Poetry.Vol. 3, No. 1 (Winter, 1965), pp. 9-18. West Virginia University Press.

11 McGann, Jerome J. "Commentary for Venus Verticordia (For a Picture)". The Rossetti Archive.2008. Web.

12 McGann, Jerome J. "Commentary for Venus Verticordia (For a Picture)". The Rossetti Archive.2008. Web.

13 "Pre-Raphaelite Challenges to Victorian Canons of Beauty".pp. 30

14 The Rossetti Archive. Venus Verticordia. (For a Picture.)

15 "Woman with Vessel."The Rossetti Archive.1863-1864.

16 Need, Lynn. "The Magdalen in Modern Times: The Mythology of the Fallen Woman in the Pre-Raphaelite Painting."Oxford Art Journal.Vol 7 (1984):26-37. Web.

17 Need, Lynn. "The Magdalen in Modern Times: The Mythology of the Fallen Woman in the Pre-Raphaelite Painting."Oxford Art Journal.Vol 7 (1984):26-37. Web.

18 Need, Lynn. "The Magdalen in Modern Times: The Mythology of the Fallen Woman in the Pre-Raphaelite Painting."Oxford Art Journal.Vol 7 (1984):26-37. Web.

19 Helen Rossetti Angeli. Dante Gabriel Rossetti His Friends and Enemies. (London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd., 1949)

20 William Michael Rossetti. Rossetti Papers, 1862-1870.London: General Books LLC, 2009.

21 "Pre-Raphaelite Challenges to Victorian Canons of Beauty". pp. 31

Links

Page 2

" "Commentary for Venus Verticordia (For a Picture)"" http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/4-1868.s173.raw

""Commentary for Venus Verticordia (For a Picture)"." http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/4-1868.s173.raw

Page 3

"Venus Verticordia. (For a Picture.)" http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/4-1868.s173.raw.html [Commentary for Venus Verticordia. (For a Picture.)]